-The Arts Fuse

This biography of Keith Haring is a compendium of vivid, first-person narratives that provide an engaging insider’s perspective on the artist’s life.

Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring by Brad Gooch. HarperCollins, 512 pages, $42.

Brad Gooch is an esteemed memoirist, novelist, and biographer of such literary figures as Rumi, Flannery O’Connor, and Frank O’Hara. His latest book is a compelling analysis of the remarkable legacy of visual artist Keith Haring.

Gooch was a contemporary of Haring — they inhabited the same queer mise-en-scène in 1980’s New York. He draws on this on-the-spot knowledge to good effect. Much has been written about Haring from an art history perspective, but Gooch adds immeasurably to the literature with this sensitive and engaging contextualized portrait that examines the life and times of the iconic artist.

The biographer was given full access to Haring’s archives and interviewed more than 200 people. The result is a compendium of vivid, first-person narratives that provide an engaging insider’s perspective on the artist’s life. Because he focuses on friends and colleagues, Gooch delivers less academic artspeak about the work and more backstories about his inspirations and frustrations.

Growing up in Kutztown, PA with working class parents and three sisters, Haring described himself as being a “little nerd.”Even as a young child he often doodled abstract cartoons with his engineer dad. In middle school, Haring had a paper route and was briefly a Jesus-freak. He became a bit of a hippie in high school and began experimenting with drugs.

After graduating, Haring briefly went to Pittsburgh to study art, but landed in New York in 1978. Gallery assistant, busboy, and club doorman were some of his early jobs as he attended School of the Visual Arts for two semesters.

At that time, the bankrupt city was under siege: its many problems included high crime and unemployment, burned-out blocks, power outages, and crumbling infrastructure. Stuck in the accumulating detritus, artists in all disciplines took the opportunity to create in polyglot, do-it-yourself ways. Haring eagerly jumped into the churn.

Attracted to the emerging graffiti scene, Haring began drawing images of crawling children and barking dogs on outdoor walls and in public spaces. He also posted Xeroxed agitprop broadsheets — a strategy inspired by William Burroughs’ cut-up methods.

Haring found a kindred tribe in the burgeoning club scene in the East Village. Gooch details the gonzo performances, installations, and experimental videos he participated in with friends — the then unknown Kenny Scharf, Madonna, Ann Magnuson, and Jean-Michel Basquiat — at such venues as Club 57 and the Mudd Club.

Haring’s public profile increased enormously after he began drawing with white chalk on the blank advertising panels on subway station walls. He’d jump off a train and sketch in full public view, all the while furtively avoiding arrest. Under these sped-up circumstances, his pictographic imagery of zapping spaceships, pulsing TV’s, barking dogs, crawling babies, leaping porpoises, and smiling faces matured.

Over the next five years, it is estimated he drew over 5,000 chalk drawings (all unsigned) throughout New York City’s boroughs. Photographer Tseng Kwong Chi documented many of his underground performative actions. Eventually, some of these drawings were digitized for a Time Square electronic billboard show.

Despite the growing attention, an early review of Haring’s work in Artforum (1981) was somewhat dismissive: “The Radiant Child on the button is Haring’s Tag. It is a slick Madison Avenue colophon. It looks as if it’s always been there. The greatest thing is to come up with something so good it seems as if it’s always been there, like a proverb.” In contrast, artist Roy Lichtenstein was more affirming: “There just isn’t a false move. It’s all so beautifully devised.”

Galleries, collectors, and museums began to take note of Haring’s growing notoriety. His first one-person gallery show took place in 1982. A year later, the artist was featured in the Whitney Museum biennial. Invitations soon followed from institutions in Europe, Australia, and Japan.

In 1983, Andy Warhol befriended him. Haring began to emulate the artist. They spoke on the phone regularly, often partied together at night, collaborated, and traded artworks. When Warhol died, Haring stated, “Whatever I’ve done would not be possible without Andy.”

As demand for Haring’s work increased, he robustly expanded his output to ink drawings, woodcut prints, paintings on tarpaulins and wood, aluminum sculptures, theatrical sets, and costumes as well as large-scale outdoor sculptures for playgrounds and murals for inner city walls, clubs, and children’s hospitals across the world. Haring was dedicated to making his art accessible to a wide audience, outside of the elitist, insular domain of curators, galleries, and museums.

Whatever the medium or scale, Haring maintained the ethos of his early subway drawings: no preparation, no preliminary sketches, just sure-handed strokes in his inimitable style. Interviews with gallerists tell a repeated tale: Haring would sequester himself in the exhibition space days before an opening, creating the entire show en masse. Often, the paint was still drying as the public was entering.

Throughout his life, Haring surrounded himself with kids. Young graffiti artists partied with him in his homes and studios. He collaborated with teenager tagger, LA II (Angel Ortiz), embellishing ready-made statues with hieroglyphic images and worked with 1,000 students in an enormous mural celebrating the Statue of Liberty (1986). In Gooch’s biography, we also learn more about the private side of Haring’s loving relationship with multiple godchildren around the world.

Sex, love, and drugs were also a huge factor in Haring’s life (deliciously detailed in Gooch’s reporting). He met his first significant lover, Juan Dubose, at the St. Mark’s Baths. Every weekend the pair went to The Paradise Garage — a club primarily for Black and Latino gay men. No alcohol was served, though many of the partygoers used hallucinogenic enhancements as they danced through the night. Madonna previewed two unreleased songs at the artist’s 26th birthday party (1984) at the venue — only to be upstaged by Diana Ross serenading Haring with “Happy Birthday.”

Trying to maintain accessibility to his work as prices for his art soared, Haring opened his Pop Shop (1986) in Manhattan, where he sold pins, T-shirts, calendars, watches, magnets, and prints. Critics trashed him for this, calling him “a disco-decorator.” While it was never a money-maker, the Pop Shop remained open until 2005 — and it maintains an online presence today. A Pop Shop in Tokyo was less successful; it closed after a year.

Even as his fame grew, Haring remained dedicated to grass-roots activism: designing posters for anti-nuke rallies, anti-apartheid protests, safe sex promotions, and events for a myriad of LGBTQ causes. During 1985’s Live Aidbenefit for famine relief in Ethiopia Haring painted on stage as Tina Turner, Michael Jackson, and Mick Jagger sang.

While working in Tokyo in 1988, Haring noticed purple lesions on his leg; his HIV status was confirmed upon returning home. Using his celebrity as a bully pulpit, he publicly announced that he was living with AIDS in Rolling Stone a year later: “In a way it’s really liberating… Part of the reason that I’m not having trouble facing the reality of death is that it’s not a limitation… Everything I’m doing right now is exactly what I want to do.”

Rather than slowing down after his diagnosis, Haring ramped up his artmaking and political activity. In his journals at the time he described his life as “working obsessively and constantly every day… the only time I am happy is when I am working.”

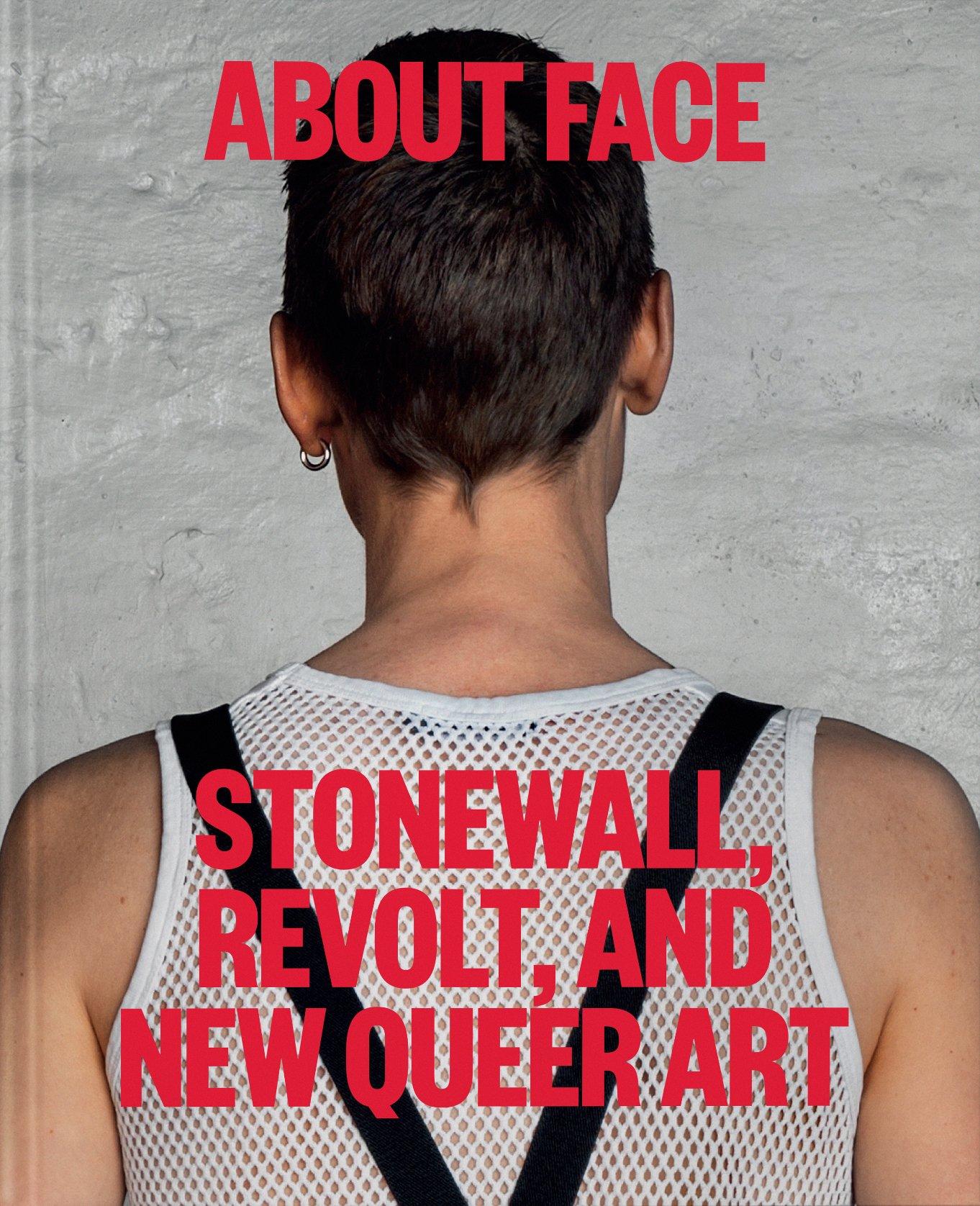

To celebrate the 20th anniversary of Stonewall Riots in an 1989 exhibition at New York’s Lesbian and Gay Community Center, Haring painted the men’s bathroom on the second floor with his “Once Upon A Time” mural, which celebrates the pre-AIDS world of unbridled gay male sexuality.

Haring died in 1990 at the age of 31. His memorial service at St. John the Divine Cathedral in Manhattan was attended by “more than a thousand invited guests.” Soprano Jessye Norman sang, choreographer Molissa Fenley danced, and actor Dennis Hopper eulogized. Kenny Scharf and Ann Magnuson were among the less reverent at the ceremony, joking that “Keith would be really bored right now,” as they recreated some “shtick and act” from Haring’s Club 57 days.

Ann Temkin, the curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, testifies to the ever-growing interest in Haring’s work after his death: “It’s a sort of truism that more radical work needs about thirty years for everyone to catch up and for the work to look as if it’s contemporary at that moment… His work can seem timeless now.”

In his endnote, Gooch’s succinctly articulates the transcendent power of Haring’s example and work: “In our own era of engagement by so many artists with any available surface; with personal icons and licensing; with activism, collaboration, communication; and with the fostering of community, Keith seems more than ever one of us.”